Things I Learned - October 2025

👻

Hello and welcome to a belated October edition of Things I Learned. Here is what I learned this month.

Things I Learned

Halloween is illegal in Iran. (source)

Every year since 1930, more people have arrived in America than have left. (source)

The reason taking a cap off a pen makes it wet again is because it draws out ink from the reservoir through suction. (source)

Before the discovery of oil in 1960, the primary industry in Dubai and the rest of the UAE was pearl-diving. (source)

Whales breastfeed. (source)

The reelection rate in the U.S. Congress (i.e. the percentage of incumbent members who run for and win reelection to their seats) is 96%. (source)

Ferrero, the manufacturer of Nutella, consumes a quarter of global hazelnut production.1 (source)

The word “gossip” originally referred to a close friend or relative invited to a birth, who would help the mother during labor. Because such events were often filled with idle conversation, it later took on its modern meaning. (h/t, source)

Only about 15% of US men are taller than 6 ft. (source)

During Wilt Chamberlain’s 100 point game — the highest scoring game in NBA history — 28 of his points were underhanded free-throws. (source)

US military spending, measured either as a percent of GDP or as a percent of total government spending, has consistently trended downwards over time, and is currently the lowest it has been in 60 years. (source, source)

More Americans played pickleball last year than baseball. (source)

The country with the world’s most oil reserves is Venezuela, well above Saudi Arabia, and with nearly as much as Russia, the USA, and Canada combined. (source)

While you cannot trademark a recipe, you can trademark the specific shape or configuration of a food product.2 (source)

The little metal wire cage that fits over the cork of a bottle of champagne is called a muselet.3 (source)

A Waymo cannot get a ticket. (source)

There are no weight divisions in sumo wrestling. (source)

Things I Liked this Month

The trivia at Farm.One in Prospect Heights, where one of the rounds is “taste-based,” i.e. you have to guess the plant based on the taste of it.

All of the FT’s excellent coverage of the First Brands fiasco.

Game 7 of the World Series.

Many of the tributes to Daniel Naroditsky, whose passing is a great loss to the chess community.

Some Belated Reflections on The Economist

As many of you know, I spent the summer at The Economist as a Marjorie Deane Fellow in financial journalism. Six months of journalism hardly makes me an authority on the profession, but enough people have asked how I found the experience that I thought a short post-mortem was warranted. I was also inspired by Arjun Ramani’s excellent reflection on his own time there, and wanted to write something in a similar spirit.4

Like Arjun, I had never seriously expected to be a journalist. Prior to The Economist, my journalistic background was limited to (i) briefs forays at a high school/college periodicals and (ii) early blog posts that I don’t think anyone read. By the time I started my PhD, my relationship with journalism was primarily as a devoted consumer of carefully curated finance newsletters (Money Talks, Alphaville, Unhedged, Markets A.M., etc.) which I hoped might spark an idea for a great academic paper.

The great academic paper never came; the opportunity at The Economist fortunately did. I saw a posting for a Marjorie Deane Fellowship; applied with an article that I spent far too much time trying to rewrite in the style of the magazine; and one (somewhat involved) interview later I was pleased to learn I received the offer. On March 18, I showed up at the Adelphi offices in London and began my 6 month fellowship.

Some scattered reflections:

I understand why so many journalists describe their job as ideal. The job, quite literally, consists of reading widely, talking to people about what they do, and writing what you think about the world. Most of us already do a version of this for free.

I was often asked whether I got to choose what I wrote. The answer is (mostly) yes. Every week or so I would pitch a handful of ideas to my editor, and he would choose one or two. Occasionally I was asked to write on a particular topic, but even then I had the option to decline.

A common bit of advice you hear in academia for finding paper ideas is to read the news to find topics that journalists/practitioners are talking about, but academics aren’t. At The Economist, I was doing a sort of reverse arbitrage: take topics that were getting traction in academic circles, and write them up for the popular press.

That approach comes with two challenges. The first is that there are many topics that academics care about, and the public doesn’t (e.g., convenience yields). Learning how to write in a way that convinces readers something is an important topic is an underrated skill. The second challenge is that many topics popular in academia are simply not newsworthy. A lot of my discussions with my editor involved him asking “Why now? why this week?” I often struggled to come up with a good answer.

The most unnatural adjustment was adapting my writing style to that of The Economist. I’m not referring to the witty and droll “voice” of my articles (which I mostly owe to my witty and droll editors), but more to the overall posture of articles. Perhaps due to graduate school, I was used to a very clinical style of writing: investigate an issue methodically, hedge frequently, don’t express an opinion, don’t bring in politics, don’t use adjectives, and certainly don’t tell people how to think. Of course, none of that really works at a publication like The Economist.

The new writing style was so unfamiliar to me that, at the beginning of my internship, I started maintaining a separate copy of how I would write each of my articles as if I were writing it for my personal blog. I would sometimes send this version of an article to my family instead of the published ones. (Not sure they read either version).

A big part of journalism is talking to people. Many of my fellow correspondents would speak with 5-10 sources a week. Most of these conversations weren’t for a specific article, but rather to get a sense of what people in industry were thinking. I was very bad at this, not only because my network was much smaller, but also because I was so used to obtaining information by reading papers.

Interviewing is its own craft. Plenty of smart people do not answer questions directly (sometimes because they can’t, sometimes because they won’t), and learning how extract useful information or guide a conversation is a skill.

I gained a deeper respect for journalists who write regularly and frequently — Matt Levine, Matt Yglesias, Robert Armstrong, Spencer Jakab, etc. I understand that many such publications are operations involving more than one person, but writing on schedule (which includes idea generation, research, writing, fact checking, etc.) is harder than it looks.

If writing seems like a lot of work, editing is more. This was something I didn’t really appreciate going in. My first week on the job, I asked a coworker what topics my editor writes on. When she responded that he doesn’t write, I asked (earnestly) what he did the other days of the week. Little did I know! Editors curate sections, solicit ideas,

babysitdiscuss articles with writers, edit the articles, coordinate with graphics teams, illustrators, fact checkers, layout team, newsletter writers, etc., all on a weekly schedule and responding in real-time to the news. The editors regularly worked 10+ hour days, much more than the writers.On that note, I found the editing process at The Economist to be quite exceptional. I know from experience that it is easy to be a lazy editor, where passable writing makes it through with a few tweaks. It is much harder to cut several hundred words while improving clarity and preserving substance. If my writing was ever any good, it owed as much or more to my editors as to me.

The editors spend a lot of time thinking about how to structure the magazine as a whole, what articles work well together, and what issues should go what week. I often wondered whether such planning was necessary, and how much quality would suffer if the magazine just used the best (non-overlapping) articles each week.

A weekly schedule may seem infrequent from the outside, but it is quite rushed. For a magazine to appear in bookshelves on Friday, it must be sent to the printers by Thursday noon, which means final drafts must be in Wednesday evening at the latest, and so first drafts should be really be in by Tuesday to allow for fact checking / editing. Since planning for the subsequent week’s issue happens on Friday afternoon, there isn’t all the much time to research/write.

I was surprised by how frequently correspondents rotate beats (countries, topics, sections, etc.). I still don’t really understand this and am not convinced it’s efficient. That said, the “beats” at The Economist are very broad: I wrote about everything from retail investing to sovereign wealth funds to the airline industry to the economics profession.

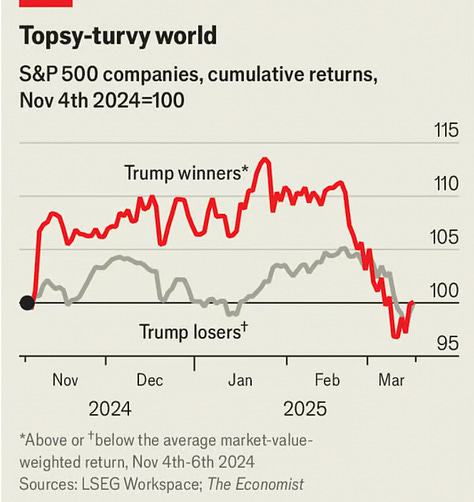

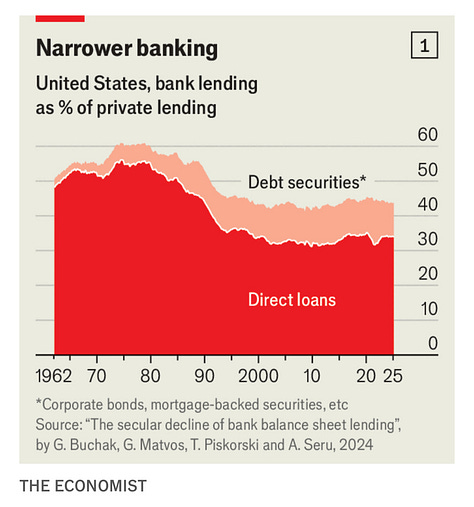

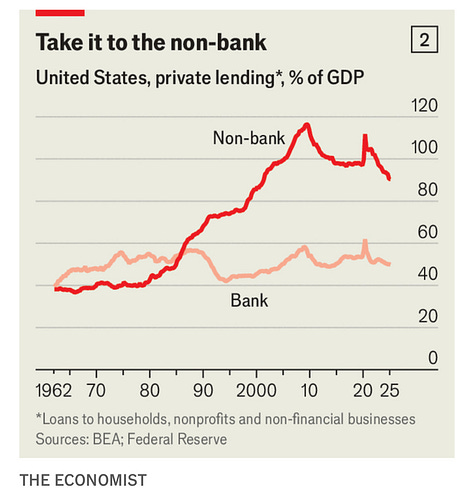

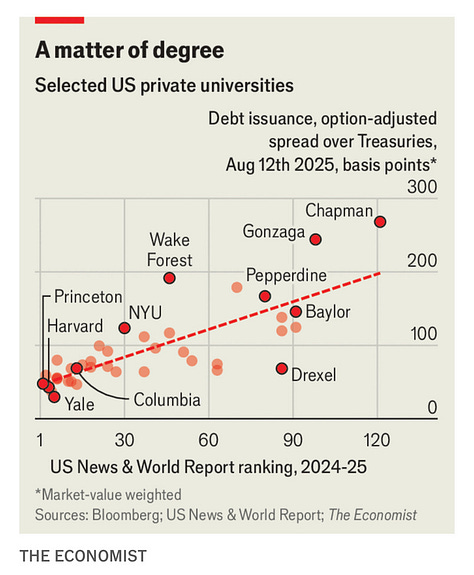

The charts produced by The Economist are, in my view, the best of any publication. A couple of common questions: (1) I only partially produced my own graphs — I would send a mock-up, and the graphics team would turn it into something far better; (2) no, The Economist does not typically rely on a built-in theme on top of a standard coding language the way ggplot does. The workflow resembles a wsywig system in which the graphics team can upload data to an in-house program and select the graph type, with a lot of labeling done in Adobe ex post.

If you’re ever unsure if no one is reading your articles — and for a publication with no bylines and no online comment section, I often wondered this! — observe what happens when you write something with a minor ambiguity or mistake.

What the The Economist does best is (a) big picture articles that provide a new/ useful/clever/humorous framing on a well known issue or (b) deep dives that explain why something in the world is how it is. A couple examples from my colleagues: teflon capitalism, how walmart took over the world; the economics of superintelligence, factory work is overrated. I would have liked to write an article like this (and a leader, a special report, a podcast, etc.) but I suppose that will have to wait for my return to journalism.

I was sometimes asked what article I was most proud of. I think it was my article on student debt, not because it was my best article (it wasn’t), but because it was an article I took on without any prior knowledge of the issue and had to learn from scratch. In general, I found it very hard to judge the quality of my own articles, if only because I was sufficiently tired of them by the time I submitted them.

Einstein observed that people love chopping wood, because “in this activity one immediately sees results.” Journalism feels much the same. To write something on a Wednesday and see it on a newsstand on Friday was an immensely gratifying experience.

There’s lot more I could say, but one of the many lessons I’ve learned from my experience is to keep my writing brief. I’ll simply end by saying (once more) it’s a fantastic job, and the publication is currently hiring a finance writer if you or anyone you know is interested.

Miscellaneous Photos from The Economist

Finally

That’s all from me this month, the highlights of which were a trip to Chicago, placing first in my age group in the Shelter Island 5K race, attending a tennis retreat with friends in upstate New York, and meeting Bryan Cranston.

Have a happy November (my birthday month 👀).

I also found this excerpt from their Wikipedia page interesting: “The company places great emphasis on secrecy, reportedly to guard against industrial espionge. It has never held a press conference and does not allow media visits to its plants. Ferrero’s products are made with machines designed by an in-house engineering department.”

Close readers of this blog might remember an adjacent fact from May 2025: “In the US, it is not possible to copyright a recipe (i.e a list of ingredients); however you can apply to copyright a recipe if it “is accompanied by substantial literary expression””

Apparently every muselet requires exactly 6 twists to open? I’m not sure I believe this.

I believe some of my colleagues subscribe, so I suppose you’ll have to interpret with due Straussianism.

This is the only newsletter I regularly look forward to.

I always learn right along with you!